Thirty-five arrived like a thief in the night. No ceremony. No parade. Just a silent nudge in the ribs saying, “Psst, wake up, you’re old now.” The day before, I was scrolling through Instagram watching people my age posing with spouses and children on perfect lawns with perfect smiles. White picket fence dreams. I double-tapped and scrolled on, wondering when my turn would come. Then I remembered – not everyone gets dealt that hand.

That’s when I decided to buy the container.

The real estate agent looked at me like I had asked for a spaceship when I said I wanted land in Kiambu, not far from the city, but just far enough. A place where the air doesn’t taste like exhaust and broken dreams. She kept showing me developments with names like “Paradise Gardens” and “Serene Heights” – those places where houses stand shoulder to shoulder like soldiers at attention, and you can hear your neighbor sneeze through the wall.

“No. I want space. Just space.” I finally told her.

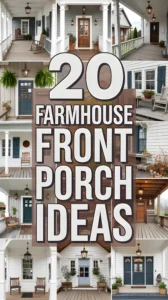

Three weeks later, I stood on a small hill overlooking a valley of tea plantations, watching the morning mist curl between the rows like ghost fingers. Two acres of possibility. The agent was skeptical about my container house plan. “You sure about this?” she asked, her face scrunched up like I had suggested living in a cardboard box. I signed the papers anyway.

The container arrived on a Tuesday. A massive, rumbling lorry struggled up the dirt road carrying what would become my home – a 40-foot metal box, once used to transport car parts from Japan. The driver, a Kikuyu man with a weather-beaten face and calloused hands, watched as they offloaded it onto the concrete foundation I had prepared.

“Hii ni nyumba?” he asked, laughing.

“Ndio,” I replied, which exhausted my Kikuyu vocabulary.

He looked at me, head tilted like a curious bird. “Wewe ni Luo, sivyo?”

I nodded, bracing myself for what usually follows. The politics, the stereotypes, the jokes.

“Wajamaa wa Luo,” he chuckled, shaking his head. “Mnapenda vitu za ajabu. Lakini hii ni mawazo nzuri.”

I wasn’t expecting that. A compliment. He thought it was a good idea. Before leaving, he pointed to a cluster of buildings in the distance. “Hiyo ni kijiji yangu. Kama unataka nyama, mimi nina mbuzi nzuri.” He had good goats for nyama choma. Of course he did. Everybody here seemed to have goats.

That night I slept in the container with just a mattress on the floor, a solar-powered lamp, and a bottle of Jameson. The metal walls amplified every sound – crickets became an orchestra, the wind a ghostly choir. I wondered if I had made a terrible mistake, trading my apartment in Kilimani for this metal box on a hill. But in the morning, I woke to sunlight streaming through the single window I had cut out, and a view that no penthouse in Nairobi could match.

It took three months to transform the container. I hired local fundis who looked at my architectural drawings (courtesy of YouTube tutorials and two sleepless nights) with equal parts amusement and professional offense. In the end, we compromised. They taught me about proper insulation against the Kiambu cold. I taught them about minimalism.

“Mbona hautaki closet kubwa?” they asked when I insisted on a tiny wardrobe.

How to explain that I was tired of having things? That each shirt, each pair of shoes, each gadget was a small anchor weighing me down. By thirty-five, you realize you don’t need most of what you own. The fundis nodded politely, probably thinking I was just another mad Luo with strange ideas.

By June, my container house was complete. Solar panels on the roof. A small deck made of reclaimed wood. Inside: a kitchenette, a bathroom with a composting toilet (another source of amusement for the fundis), a living area with floor-to-ceiling windows facing the valley, and a bedroom just big enough for a queen-sized bed and books. Lots of books.

The first thing I planted was bananas – not the sweet ones, but plantains. The kind my grandmother used to fry with just a hint of salt. The locals watched me dig in the red soil, their faces a mix of curiosity and mild concern. Here was a Luo, in Kikuyu country, digging like he belonged.

“Unajua kusema Kikuyu?” an old man asked, leaning on his walking stick, his face a map of wrinkles and wisdom.

“Hapana, kidogo tu,” I admitted.

He laughed, a deep rumble like distant thunder. “Sasa utajifunza.”

Yes, now I would learn. Not just Kikuyu, but other things too. How to wake up with the sun. How to listen to the land. How to be alone without being lonely.

The chickens came next. Five hens and a rooster who thought he was a guard dog. He would crow not just at dawn but whenever anyone approached my compound. I named him Marcus after Marcus Garvey – because he seemed to believe he was leading a revolution.

“Marcus, you’re just a chicken,” I would tell him when he puffed up his chest at me.

The chickens gave me eggs, company, and a routine. There’s something about having creatures dependent on you that anchors you to a place. To be responsible for something living is to commit to staying, to showing up every day.

My neighbors gradually accepted the strange Luo in the metal box. They would stop by with offerings – a basket of arrowroots, some fresh milk, avocados from their trees. I would invite them in for chai, and they would look around my container with poorly concealed fascination.

“Unaishi peke yako?” they would inevitably ask. You live alone?

The question always carried subtext. Where is your wife? Your children? At thirty-five, a man should have these things.

“Yes, alone,” I would say, and pour more tea, changing the subject.

But the truth was, I had made peace with it. The traditional family – wife, 2.5 kids, dog – might not be in my cards. My last relationship had ended a year before, when she wanted to move to the US for her career, and I couldn’t imagine leaving Kenya. Before that, there was the woman who wanted children immediately, while I was still trying to figure out who I was. And before that… well, there’s always a before that. A series of almosts.

By thirty-five, you learn that some dreams need to be reimagined. Not abandoned, just… redesigned. Like my container house.

The first time I hosted friends for nyama choma on my deck, they arrived with the skepticism of people expecting to find me living in squalor.

“Bro, when you said container house, I thought you were joking,” said Pete, my friend since university, as he explored my space, beer in hand.

“It’s so… nice,” said Amina, genuine surprise in her voice as she took in the view.

I had bought a goat from my neighbor, the lorry driver who had delivered my container. He helped me prepare it, showing me how to season it properly with salt and pepper and nothing else. “Nyama nzuri haitaji vitu mingi,” he insisted. Good meat doesn’t need many things.

As the sun set, casting the tea plantations in golden light, my friends and I sat on the deck, the smell of roasting meat in the air, cold Tuskers in hand. The conversation flowed from work to politics to the universal complexities of relationships. No one mentioned my lack of a wife or children. Instead, they seemed to envy my peace, my space, my slow mornings.

“You might be onto something,” Pete said, looking out at the valley below. “The rat race is killing us.”

Later, after they had gone, I sat alone on the deck with the last bottle of beer, watching the stars. In Nairobi, you forget how many there are. Out here, they crowd the sky like curious onlookers. I thought about turning thirty-five, about the expectations I had shed like old skin. The stoics had it right – happiness isn’t getting what you want, but wanting what you have.

My phone buzzed with a message from Amina: “Your place is amazing. But aren’t you lonely out there?”

I looked around at my container house, at the valley below, at Marcus the rooster standing guard even in the darkness. I typed back: “Not lonely. Just alone. There’s a difference.”

The Kikuyu have a saying that translates roughly to “A man without roots is like a tree in the wind.” They believe in belonging to a place, in knowing your ancestors, in being part of something larger than yourself. As a Luo in Kikuyu country, I was rootless – or so they thought.

The thing about being Luo in a predominantly Kikuyu place is that you’re always slightly foreign. Always the “other.” Even when they’re friendly – and they usually are, despite what political rhetoric might suggest – there’s an awareness of difference. You hear it in the jokes, in the questions, in the subtle ways conversation shifts when certain topics arise.

“Si nyinyi Wajaluo mnapenda siasa sana?” they would ask when politics came up. Don’t you Luos love politics too much?

Or the classic: “Mbona Wajaluo hawatahiri?” The circumcision question. Always the circumcision question.

At first, I would engage, explain, defend. But gradually, I learned to smile, to shrug, to let it go. You can spend your whole life being an ambassador for your tribe, or you can just be yourself and let them adjust their perceptions accordingly.

Six months into my container life, during a particularly heavy downpour, there was a knock at my door. It was the old man with the walking stick, soaked through, his stick sinking into the mud.

“Nimepotea ng’ombe yangu,” he said, his voice cracking with worry. His cow was missing.

I grabbed a raincoat and a torch, and we searched together, slipping in the mud, the rain beating down on us. We found the cow stuck in a ditch not far from my property, scared but unhurt. Together, we coaxed it out, the old man whispering to it in Kikuyu.

As we walked back, the old man studied me through the rain. “Wewe ni mtu wa hapa sasa,” he said quietly. You are a person of this place now.

It was the first time I felt truly accepted. Not as a curiosity, not as “the Luo in the container,” but as a neighbor. A person of this place.

Minimalism isn’t about having less; it’s about making room for what matters. My container house taught me that. With limited space, you can’t accumulate needlessly. You must choose carefully, intentionally.

The same goes for life. By thirty-five, you’ve collected enough experiences to know what serves you and what doesn’t. Enough relationships to recognize patterns. Enough failures to understand resilience.

Stoicism teaches acceptance of what is, not endless yearning for what isn’t. It’s about finding tranquility in the face of chaos, about focusing on what you can control and releasing what you can’t.

My simple life in Kiambu – with my chickens, my plantains, my metal house on a hill – is an exercise in both minimalism and stoicism. It’s not perfect. The roof leaks sometimes. Marcus the rooster wakes me up too early. The solar power fails during extended cloudy periods.

But I’ve never slept better. Never felt more present. Never been more at peace with who I am and who I’m not.

Sometimes, in the evening, as the sun sets and the tea pickers make their way home from the plantations, I sit on my deck and think about the life I thought I would have versus the one I actually have. The gap between the two used to feel like failure. Now it feels like freedom.

At thirty-five, I’ve learned that the traditional path isn’t for everyone. That family can be defined in many ways. That home isn’t necessarily where you were born, but where you decide to plant yourself.

And sometimes, home is a metal box on a hill, surrounded by tea plantations, chickens, and neighbors who no longer see you as the Luo in the container, but just as the man who lives up there. The man who comes to their weddings and funerals. The man who speaks terrible Kikuyu but tries anyway. The man who found his place.

Last week, a young couple stopped by my container. They had heard about “the container house” and wanted to see it for themselves. The woman was Kikuyu, the man Luo. They were thinking of doing something similar, of escaping the city.

As I showed them around, I recognized in them the same restlessness I had felt a year ago. The same questioning of conventional paths. The same desire for space and silence and simplicity.

“Does it get lonely?” the woman asked, echoing Amina’s question from months before.

I thought about my morning routine – waking with the sun, feeding the chickens, tending to my small shamba, writing for a few hours, walking down to the village for supplies, exchanging greetings with neighbors, sitting on my deck watching the sunset.

“Sometimes,” I admitted. “But mostly, it’s just quiet. And after years of noise, quiet feels like a gift.”

As they were leaving, the man lingered behind. “You know what they say about us Luos,” he said, a hint of defensiveness in his voice.

I smiled. “I know what they say. Let them say it. Just build your container anyway.”

He nodded, understanding. It wasn’t just about a house. It was about defining your own path. About finding your peace in unlikely places. About turning thirty-five and realizing that the life you’re supposed to want might not be the one that will make you happy.

That night, under a sky full of stars, with Marcus the rooster roosting nearby and the distant lights of Nairobi twinkling like a separate universe, I felt something close to contentment. Not the frantic happiness that comes from achievement or acquisition, but something deeper. A settling.

The metal box on the hill isn’t just a home. It’s a statement. It says: I choose this life. I choose this place. I choose this peace.

At thirty-five, that’s enough.